text and photo by Dave Roeder, MMR

The NMRA achievement program has a requirement that the applicant build a total of eight pieces of rolling stock. Four of these must be scratch built according to the regulations as written. The other four must be super detailed (also according to the regulations).

One of the eight cars must be a passenger car. Additional requirements are that the four scratch built cars must all be different designs. Four wood box cars of the same design, but lettered for different railroads is not allowed.

Research, Planning and Design

After reviewing the NMRA information, I decided to model early cars from the time period just after the civil war. This period from 1870 to 1890 and up to 1900 saw the beginning of standards for couplers and air brakes.

Since I was not familiar with civil war era cars, I contacted Bob Amsler who I knew was researching this period. Bob is also a model railroader and serves as legal representation for the NMRA nationally. Bob put me on to several reference books on the Civil War era and the United States Military Railroad as it was known back during the Civil War. In addition there were two volumes of The American Freight Car by John H. White [1993] and The American Passenger Car also by John H. White [1978] that gave details of the technological advances throughout the development of American Railroads. With titles and author names in hand, I went to the Barriger collection at the University of Missouri, St. Louis and was able to copy pages from these books. Once I had the design information, I created detailed drawings for 3 freight cars and 1 passenger car that I would scratch build to qualify for the AP certificate in Cars. I drew the four cars in “O” scale (.250″ = 1′ 0″). These four drawings were the basis for the construction.

Materials

I have always built structures and modified rolling stock using styrene so it was a simple matter to purchase Evergreen Styrene strip, rod and sheet to suit the sizes required. Early freight cars were of wood design, so even the frames were simple straight shapes. Large structural pieces such as the bolsters were made from .250″ square stock. Other frame parts such as sills and cross members were made from strip stock of the proper dimensions. Car siding is available from Evergreen in scale 3″ width scribing.

The detail parts such as grab irons and brake gear can be purchased individually, or you may go to a swap meet and purchase an old Varney, LaBelle Woodworking Co. or Liberty craftsman kit to get these parts as a set. An additional benefit of this approach is that you get a set of plans that you may use to construct your own scratch built version of a car. The only drawback is that the AP judging gives more points for plans drawn by the person building the car.

I made bending jigs to fabricate simple items such as grab irons. The brake rigging on early cars was much more primitive than on cars from the 1930’s. Suppliers such as Tichy Train Group, Grandt Line and Kadee offer some very nice plastic parts with a high level of detail. I went to our local detail parts hobby shop Tinkertown in Ladue, Missouri for these. In fact, I purchased all of the early style Westinghouse air brake sets in stock.

Construction

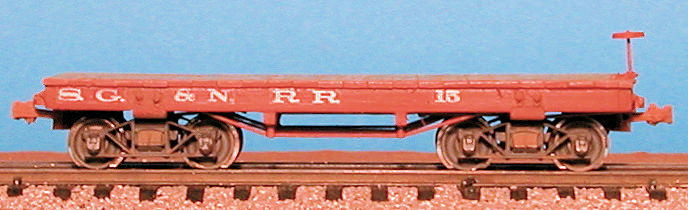

I started with the most basic of freight cars, a Carter Brothers flat car. This car was very primitive in that it had only mechanical brakes. Research revealed some of the railroads were reluctant to put any brakes on freight cars. In some cases the cars had mechanical brakes on only one truck. Passenger cars were equipped with hand brakes as early as 1845. Early freight cars were not equipped with brakes since most railroads considered this expense unnecessary. Life was cheap and safety was not on the minds of those in charge of the purse strings during this period.

Starting with the basic frame, a flat car is nothing more than a series of timbers cut to length and placed in a square jig to get 90 degree corners. Care must be taken to cut parts to exact lengths. A Northwest Shortline chopper is a good investment for this part of the job. I also use a 6″ dial caliper to insure scratch built bolster heights are within .002″ of each other.

I cut a set of planks for the decking from strip styrene. This is the easiest part of the fabrication. I drill and tap a #2-56 UNC thread for truck mounting screws in the bolsters and use a #0–80 for the coupler mounts. Note: Kadee HOn3 narrow gage coupler sets come with #0 sheet metal screws that work very well in styrene.

Grandt Line nut bolt and washer castings are available in most common sizes for details. I also found drop type grab irons made from wire. These were very easy to install using a very small amount of ACC adhesive. I use a canvas sewing needle cut off on the eye end and pressed into a 1/4″ wood dowel handle to apply the ACC at the base of the grab iron.

One step you must do when working in styrene is drilling holes for steps and grab irons. I have a set of drill bits from .013″ to .040″ in a small case. These are very handy for doing this work. I set my Uni-Mat Machining Center up as a vertical drill press and feed the drills into the work by moving the work on to the rotating drill. I find this gives better control and eliminates drill breakage. I also use an old beeswax candle to lube the drill before each hole.

If you have ever built a Tichy Train Group freight car, you now can have the pleasure of doing the same type of detail assembly work. The difference is you are assembling a “plastic kit” with individual components that you fabricated. Final assembly, paint, decals and weathering are all the same as on any kit. Once you get started, these cars go together just like any other kit except that you made all of the major parts.